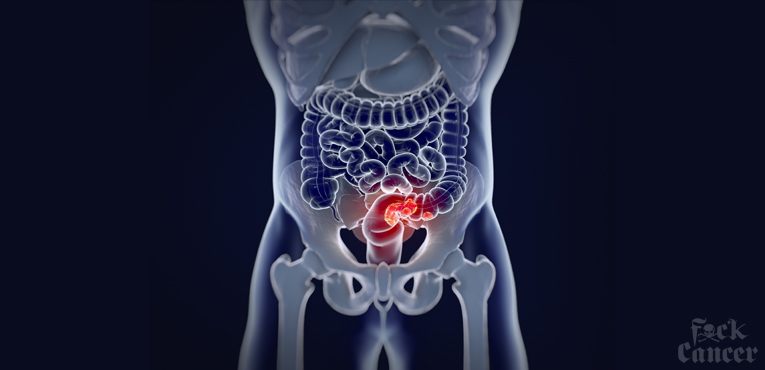

SIGNS & SYMPTOMS

Colorectal cancer might not cause symptoms right away, but if it does, it may cause one or more of these symptoms:

- A change in bowel habits, such as diarrhea, constipation, or narrowing of the stool, that lasts for more than a few days

- A feeling that you need to have a bowel movement that’s not relieved by having one.

- Rectal bleeding with bright red blood.

- Blood in the stool, which might make the stool look dark brown or black.

- Cramping or abdominal (belly) pain

- Weakness and fatigue

- Unintended weight loss.

Colorectal cancers can often bleed into the digestive tract. Sometimes the blood can be seen in the stool or make it look darker, but often the stool looks normal. But over time, the blood loss can build up and can lead to low red blood cell counts (anemia). Sometimes the first sign of colorectal cancer is a blood test showing a low red blood cell count.

Some people may have signs that the cancer has spread to the liver with a large liver felt on exam, jaundice (yellowing of the skin or whites of the eyes), or trouble breathing from cancer spread to the lungs.

Many of these symptoms can be caused by conditions other than colorectal cancer, such as infection, hemorrhoids, or irritable bowel syndrome. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENING TESTS

Screening is the process of looking for cancer in people who have no symptoms. Several tests can be used to screen for colorectal cancer (see American Cancer Society Guideline for Colorectal Cancer Screening). The most important thing is to get screened, no matter which test you choose.

These tests can be divided into 2 main groups:

- Stool-based tests: These tests check the stool (feces) for signs of cancer. These tests are less invasive and easier to have done, but they need to be done more often.

- Visual (structural) exams: These tests look at the structure of the colon and rectum for any abnormal areas. This is done either with a scope (a tube-like instrument with a light and tiny video camera on the end) put into the rectum, or with special imaging (x-ray) tests.

These tests each have different risks and benefits (see the table below), and some of them might be better options for you than others.

If you choose to be screened with a test other than colonoscopy, any abnormal test result should be followed up with a timely colonoscopy.

Some of these tests might also be used if you have symptoms of colorectal cancer or other digestive diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease.

Stool-based tests

These tests look at the stool (feces) for possible signs of colorectal cancer or polyps. These tests are typically done at home, so many people find them easier than tests like a colonoscopy. But these tests need to be done more often. And if the result from one of these stool tests is positive (abnormal), you will still need a colonoscopy to see if you have cancer.

Fecal immunochemical test (FIT)

One way to test for colorectal cancer is to look for occult (hidden) blood in the stool. The idea behind this type of test is that blood vessels in larger colorectal polyps or cancers are often fragile and easily damaged by the passage of stool. The damaged vessels usually bleed into the colon or rectum, but only rarely is there enough bleeding for blood to be seen by the naked eye in the stool.

The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) checks for hidden blood in the stool from the lower intestines. This test must be done every year, unlike some other tests (like the visual tests described below). It can be done in the privacy of your own home.

Unlike the gFOBT (see below), there are no drug or dietary restrictions before the FIT test (because vitamins and foods do not affect the test), and collecting the samples may be easier. This test is also less likely to react to bleeding from the upper parts of the digestive tract, such as the stomach.

Collecting the samples: Your health care provider will give you the supplies you need for testing. Have all of your supplies ready and in one place. Supplies typically include a test kit, test cards or tubes, long brushes or other collecting devices, waste bags, and a mailing envelope. The kit will give you detailed instructions on how to collect the samples. Be sure to follow the instructions that come with your kit, as different kits might have different instructions. If you have any questions about how to use your kit, contact your health care provider’s office or clinic. Once you have collected the samples, return them as instructed in the kit.

If the test result is positive (that is, if hidden blood is found), a colonoscopy will need to be done to investigate further. Although blood in the stool can be from cancer or polyps, it can also be from other causes, such as ulcers, hemorrhoids, or other conditions.

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT)

The guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) finds occult (hidden) blood in the stool through a chemical reaction. It works differently from the FIT, but like the FIT, the gFOBT can’t tell if the blood is from the colon or from other parts of the digestive tract (such as the stomach).

This test must be done every year, unlike some other tests (like the visual tests described below). This test can be done in the privacy of your own home. It checks more than one stool sample.

If gFOBT is chosen for colorectal screening, the American Cancer Society recommends the highly sensitive versions of this test be used.

Before the test: Some foods or drugs can affect the results of this test, so you may be instructed to avoid the following before this test:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Advil), naproxen (Aleve), or aspirin, for 7 days before testing. (They can cause bleeding, which can lead to a false-positive result.) Note: People should try to avoid taking NSAIDs for minor aches prior to the test. But if you take these medicines daily for heart problems or other conditions, don’t stop them for this test without talking to your health care provider first.

- Vitamin C more than 250 mg a day from either supplements or citrus fruits and juices for 3 to 7 days before testing. (This can affect the chemicals in the test and make the result negative, even if blood is present.)

- Red meats (beef, lamb, or liver) for 3 days before testing. (Components of blood in the meat may cause a positive test result.)

Some people who are given the test never do it or don’t return it because they worry that something they ate may affect the test. Even if you are concerned that something you ate may alter the test, the most important thing is to get the test done.

Collecting the samples: You will get a kit with instructions from your health care provider’s office or clinic. The kit will explain how to take stool samples at home (usually samples from 3 separate bowel movements are smeared onto small paper cards). The kit is then returned to the doctor’s office or medical lab for testing.

When doing this test, have all of your supplies ready and in one place. Supplies typically include a test kit, test cards, either a brush or wooden applicator, and a mailing envelope. The kit will give you detailed instructions on how to collect the stool samples. Be sure to follow the instructions that come with your kit, as different kits might have different instructions. If you have any questions about how to use your kit, contact your health care provider’s office or clinic. Once you have collected the samples, return them as instructed in the kit.

If the test result is positive (if hidden blood is found), a colonoscopy will be needed to find the reason for the bleeding.

A FOBT done during a digital rectal exam in the doctor’s office (which only checks one stool sample) is not enough for proper screening, because it is likely to miss most colorectal cancers.

Stool DNA test

A stool DNA test (also known as a multitargeted stool DNA test[MT-sDNA] or FIT-DNA) looks for certain abnormal sections of DNA from cancer or polyp cells and also for occult (hidden) blood. Colorectal cancer or polyp cells often have DNA mutations (changes) in certain genes. Cells with these mutations often get into the stool, where tests may be able to find them. Cologuard, the only test currently available in the US, tests for both DNA changes and blood in the stool (FIT).

This test should be done every 3 years and can be done in the privacy of your own home. It tests a full stool sample. There are no drug or dietary restrictions before taking the test.

Collecting the samples: You’ll get a kit in the mail to use to collect your entire stool sample at home. The kit will have a sample container, a bracket for holding the container in the toilet, a bottle of liquid preservative, a tube, labels, and a shipping box. The kit has detailed instructions on how to collect the sample. Be sure to follow the instructions that come with your kit. If you have any questions about how to use your kit, contact your doctor’s office or clinic. Once you have collected the sample, return it as instructed in the kit.

If the test is positive (if it finds DNA changes or blood), a colonoscopy will be need to be done.

Visual (structural) exams

These tests look at the inside of the colon and rectum for any abnormal areas that might be cancer or polyps. These tests can be done less often than stool-based tests, but they require more preparation ahead of time, and can have some risks not seen with stool-based tests.

Colonoscopy

For this test, the doctor looks at the entire length of the colon and rectum with a colonoscope, a flexible tube about the width of a finger with a light and small video camera on the end. It’s put in through the anus and into the rectum and colon. Special instruments can be passed through the colonoscope to biopsy (take a sample) or remove any suspicious-looking areas such as polyps, if needed.

To see a visual animation of a colonoscopy as well as learn more details about how to prepare for the procedure, how the procedure is done, and potential side effects, see Colonoscopy.

(Note: This test is different from a virtual colonoscopy (also known as CT colonography), which is a type of CT scan.)

CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy)

This test is an advanced type of computed tomography (CT) scan of the colon and rectum that can show abnormal areas, like polyps or cancer. Special computer programs use both x-rays and a CT scan to make 3-dimensional pictures of the inside of the colon and rectum. It does not require sedation (medicine to sleep) or any type of instrument or scope being put into the rectum or colon.

This test may be useful for some people who can’t have or don’t want to have a more invasive test such as a colonoscopy. It can be done fairly quickly, but it requires the same type of bowel prep as for a colonoscopy.

If polyps or other suspicious areas are seen on this test, a colonoscopy will still be needed to remove them or to explore the area fully.

Before the test: It’s important that the colon and rectum are emptied before this test to get the best images. You’ll probably be told to follow the same instructions to clean out the intestines as someone getting a colonoscopy.

During the test: This test is done in a special room with a CT scanner. It takes about 10 minutes. You may be asked to drink a contrast solution before the test to help identify any stool left in the colon or rectum, which helps the doctor when looking at the images. You’ll be asked to lie on a narrow table that’s part of the CT scanner, and will have a small, flexible tube put into your rectum. Air is pumped through the tube into the colon and rectum to expand them to provide better pictures. The table then slides into the CT scanner, and you’ll be asked to hold your breath for about 15 seconds while the scan is done. You’ll likely have 2 scans: one while you’re lying on your back and one while you’re on your stomach or side.

Possible side effects and complications: There are usually few side effects after this test. You may feel bloated or have cramps because of the air in the colon and rectum, but this should go away once the air passes from the body. There’s a very small risk that inflating the colon with air could injure or puncture it, but this risk is thought to be much less than with colonoscopy. Like other types of CT scans, this test also exposes you to a small amount of radiation.

Flexible sigmoidoscopy

A flexible sigmoidoscopy is similar to a colonoscopy except is doesn’t examine the entire colon. A sigmoidoscope (a flexible, lighted tube about the thickness of a finger with a small video camera on the end) is put in through the anus, into the rectum and then moved into the lower part of the colon. But the sigmoidoscope is only about 2 feet (60cm) long, so the doctor can only see less than half of the colon and the entire rectum. Images from the scope are seen on a video screen so the doctor can find and possibly remove any abnormal areas.

This test is not widely used as a screening tool for colorectal cancer in the United States.

Before the test:

The colon and rectum should be emptied before this test to get the best pictures. You’ll probably be told to follow similar instructions to clean out the intestines as someone getting a colonoscopy.

During the test: A sigmoidoscopy usually takes about 10 to 20 minutes. Most people don’t need to be sedated for this test, but this might be an option you can discuss with your doctor. Sedation may make the test less uncomfortable, but you’ll need some time to recover from it and you’ll need someone with you to take you home after the test.

You’ll probably be asked to lie on a table on your left side with your knees pulled up near your chest. Before the test, your doctor may put a gloved, lubricated finger into your rectum to examine it. The sigmoidoscope is first lubricated to make it easier to put into the rectum. Air is then pumped into the colon and rectum through the sigmoidoscope so the doctor can see the inner lining better. This may cause some discomfort, but it should not be painful. Be sure to let your doctor know if you feel pain during the procedure.

If you are not sedated during the procedure, you might feel pressure and slight cramping in your lower belly. To ease discomfort and the urge to have a bowel movement, it may help to breathe deeply and slowly through your mouth. You’ll feel better after the test once the air leaves your bowels.

If any polyps are found during the test, the doctor may remove them with a small instrument passed through the scope. The polyps will be looked at in the lab. If a pre-cancerous polyp (an adenoma) or colorectal cancer is found, you’ll need to have a colonoscopy later to look for polyps or cancer in the rest of the colon.

Possible complications and side effects: You might see a small amount of blood in your bowel movements for a day or 2 after the test. More serious bleeding and puncture of the colon or rectum are possible, but they are not common.

GUIDELINES FOR COLORECTAL CANCER SCREENINGS

The American Cancer Society recommends that people at average risk* of colorectal cancer start regular screening at age 45. This can be done either with a sensitive test that looks for signs of cancer in a person’s stool (a stool-based test), or with an exam that looks at the colon and rectum (a visual exam). These options are listed below.

People who are in good health and with a life expectancy of more than 10 years should continue regular colorectal cancer screening through the age of 75.

For people ages 76 through 85, the decision to be screened should be based on a person’s preferences, life expectancy, overall health, and prior screening history.

People over 85 should no longer get colorectal cancer screening.

*For screening, people are considered to be at average risk if they do not have:

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps

- A family history of colorectal cancer

- A personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease)

- A confirmed or suspected hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome, such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Lynch syndrome (hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC)

- A personal history of getting radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer

PEOPLE AT INCREASED OR HIGH RISK

People at increased or high risk of colorectal cancer might need to start colorectal cancer screening before age 45, be screened more often, and/or get specific tests. This includes people with:

- A strong family history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps (see Colorectal Cancer Risk Factors)

- A personal history of colorectal cancer or certain types of polyps

- A personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease)

- A known family history of a hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome such as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) or Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer or HNPCC)

- A personal history of radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer

The American Cancer Society does not have screening guidelines specifically for people at increased or high risk of colorectal cancer. However, some other professional medical organizations, such as the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer (USMSTF), do put out such guidelines. These guidelines are complex and are best looked at along with your health care provider. In general, these guidelines put people into several groups (although the details depend on each person’s specific risk factors).

People with one or more family members who have had colon or rectal cancer…

Screening recommendations for these people depend on who in the family had cancer and how old they were when it was diagnosed. Some people with a family history will be able to follow the recommendations for average risk adults, but others might need to get a colonoscopy (and not any other type of test) more often, and possibly starting before age 45.

People who have had certain types of polyps removed during a colonoscopy…

Most of these people will need to get a colonoscopy again after 3 years, but some people might need to get one earlier (or later) than 3 years, depending on the type, size, and number of polyps.

People who have had colon or rectal cancer…

Most of these people will need to start having colonoscopies regularly about one year after surgery to remove the cancer. Other procedures like MRI or proctoscopy with ultrasound might also be recommended for some people with rectal cancer, depending on the type of surgery they had.

People who have had radiation to the abdomen (belly) or pelvic area to treat a prior cancer…

Most of these people will need to start having colorectal screening (colonoscopy or stool based testing) at an earlier age (depending on how old they were when they got the radiation). Screening often begins 5 years after the radiation was given or at age 30, whichever comes last. These people might also need to be screened more often than normal (such as at least every 3 to 5 years).

People with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis)…

These people generally need to get colonoscopies (not any other type of test) starting at least 8 years after they are diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease. Follow-up colonoscopies should be done every 1 to 3 years, depending on the person’s risk factors for colorectal cancer and the findings on the previous colonoscopy.

People known or suspected to have certain genetic syndromes…

These people generally need to have colonoscopy (not any of the other tests). Screening is often recommended to begin at a young age, possibly as early as the teenage years for some syndromes – and needs to be done much more frequently. Specifics depend on which genetic syndrome you have, and other factors.

If you’re at increased or high risk of colorectal cancer (or think you might be), talk to your health care provider to learn more. Your provider can suggest the best screening option for you, as well as determine what type of screening schedule you should follow, based on your individual risk.

Source: American Cancer Society, How the American cancer society fights colorectal cancer, https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/special-coverage/how-acs-fights-colon-cancer.html