Can Pancreatic Cancer Be Found Early?

Pancreatic cancer is hard to find early. The pancreas is deep inside the body, so early tumors can’t be seen or felt by health care providers during routine physical exams. People usually have no symptoms until the cancer has become very large or has already spread to other organs.

For certain types of cancer, screening tests or exams are used to look for cancer in people who have no symptoms (and who have not had that cancer before). But for pancreatic cancer, no major professional groups currently recommend routine screening in people who are at average risk. This is because no screening test has been shown to lower the risk of dying from this cancer.

Genetic testing for people who might be at increased risk

Some people might be at increased risk of pancreatic cancer because of a family history of the disease (or a family history of certain other cancers). Sometimes this increased risk is due to a specific genetic syndrome.

Genetic testing looks for the gene changes that cause these inherited conditions and increase pancreatic cancer risk. The tests look for these inherited conditions, not pancreatic cancer itself. Your risk may be increased if you have one of these conditions, but it doesn’t mean that you have (or definitely will get) pancreatic cancer.

Knowing if you are at increased risk can help you and your doctor decide if you should have tests to look for pancreatic cancer early, when it might be easier to treat. But determining whether you might be at increased risk is not simple. The American Cancer Society strongly recommends that anyone thinking about genetic testing talk with a genetic counselor, nurse, or doctor (qualified to interpret and explain the test results) before getting tested. It’s important to understand what the tests can − and can’t − tell you, and what any results might mean, before deciding to be tested.

Testing for pancreatic cancer in people at high risk

For people in families at high risk of pancreatic cancer, newer tests for detecting pancreatic cancer early may help. The two most common tests used are an endoscopic ultrasound or MRI. These tests are not used to screen the general public, but might be used for someone with a strong family history of pancreatic cancer or with a known genetic syndrome that increases their risk. Doctors have been able to find early, treatable pancreatic cancers in some members of high-risk families with these tests.

Doctors are also studying other new tests to try to find pancreatic cancer early. Interested families at high risk may wish to take part in studies of these new screening tests.

Signs and Symptoms of Pancreatic Cancer

Early pancreatic cancers often do not cause any signs or symptoms. By the time they do cause symptoms, they have often grown very large or already spread outside the pancreas.

Having one or more of the symptoms below does not mean you have pancreatic cancer. In fact, many of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by other conditions. Still, if you have any of these symptoms, it’s important to have them checked by a doctor so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Jaundice and related symptoms

Jaundice is yellowing of the eyes and skin. Most people with pancreatic cancer (and nearly all people with ampullary cancer) will have jaundice as one of their first symptoms.

Jaundice is caused by the buildup of bilirubin, a dark yellow-brown substance made in the liver. Normally, the liver releases a liquid called bile that contains bilirubin. Bile goes through the common bile duct into the intestines, where it helps break down fats. It eventually leaves the body in the stool. When the common bile duct becomes blocked, bile can’t reach the intestines, and the amount of bilirubin in the body builds up.

Cancers that start in the head of the pancreas are near the common bile duct. These cancers can press on the duct and cause jaundice while they are still fairly small, which can sometimes lead to these tumors being found at an early stage. But cancers that start in the body or tail of the pancreas don’t press on the duct until they have spread through the pancreas. By this time, the cancer has often spread beyond the pancreas.

When pancreatic cancer spreads, it often goes to the liver. This can also cause jaundice.

There are other signs of jaundice as well as the yellowing of the eyes and skin:

- Dark urine: Sometimes, the first sign of jaundice is darker urine. As bilirubin levels in the blood increase, the urine becomes brown in color.

- Light-colored or greasy stools: Bilirubin normally helps give stools their brown color. If the bile duct is blocked, stools might be light-colored or gray. Also, if bile and pancreatic enzymes can’t get through to the intestines to help break down fats, the stools can become greasy and might float in the toilet.

- Itchy skin: When bilirubin builds up in the skin, it can start to itch as well as turn yellow.

Pancreatic cancer is not the most common cause of jaundice. Other causes, such as gallstones, hepatitis, and other liver and bile duct diseases, are much more common.

Belly or back pain

Pain in the abdomen (belly) or back is common in pancreatic cancer. Cancers that start in the body or tail of the pancreas can grow fairly large and start to press on other nearby organs, causing pain. The cancer may also spread to the nerves surrounding the pancreas, which often causes back pain. Pain in the abdomen or back is fairly common and is most often caused by something other than pancreatic cancer.

Weight loss and poor appetite

Unintended weight loss is very common in people with pancreatic cancer. These people often have little or no appetite.

Nausea and vomiting

If the cancer presses on the far end of the stomach it can partly block it, making it hard for food to get through. This can cause nausea, vomiting, and pain that tend to be worse after eating.

Gallbladder or liver enlargement

If the cancer blocks the bile duct, bile can build up in the gallbladder, making it larger. Sometimes a doctor can feel this (as a large lump under the right side of the ribcage) during a physical exam. It can also be seen on imaging tests.

Pancreatic cancer can also sometimes enlarge the liver, especially if the cancer has spread there. The doctor might be able to feel the edge of the liver below the right ribcage on an exam, or the large liver might be seen on imaging tests.

Blood clots

Sometimes, the first clue that someone has pancreatic cancer is a blood clot in a large vein, often in the leg. This is called a deep vein thrombosis or DVT. Symptoms can include pain, swelling, redness, and warmth in the affected leg. Sometimes a piece of the clot can break off and travel to the lungs, which might make it hard to breathe or cause chest pain. A blood clot in the lungs is called a pulmonary embolism or PE.

Still, having a blood clot does not usually mean that you have cancer. Most blood clots are caused by other things.

Diabetes

Rarely, pancreatic cancers cause diabetes (high blood sugar) because they destroy the insulin-making cells. Symptoms can include feeling thirsty and hungry, and having to urinate often. More often, cancer can lead to small changes in blood sugar levels that don’t cause symptoms of diabetes but can still be detected with blood tests.

Tests for Pancreatic Cancer

If a person has signs and symptoms that might be caused by pancreatic cancer, certain exams and tests will be done to find the cause. If cancer is found, more tests will be done to help determine the extent (stage) of the cancer.

Medical history and physical exam

Your doctor will ask about your medical history to learn more about your symptoms. The doctor might also ask about possible risk factors, including smoking and your family history.

Your doctor will also examine you to look for signs of pancreatic cancer or other health problems. Pancreatic cancers can sometimes cause the liver or gallbladder to swell, which the doctor might be able to feel during the exam. Your skin and the whites of your eyes will also be checked for jaundice (yellowing).

If the results of the exam are abnormal, your doctor will probably order tests to help find the problem. You might also be referred to a gastroenterologist (a doctor who treats digestive system diseases) for further tests and treatment.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, sound waves, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of your body. Imaging tests might be done for a number of reasons both before and after a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer, including:

- To look for suspicious areas that might be cancer

- To learn how far cancer may have spread

- To help determine if treatment is working

- To look for signs of cancer coming back after treatment

Computed tomography (CT) scan

The CT scan makes detailed cross-sectional images of your body. CT scans are often used to diagnose pancreatic cancer because they can show the pancreas fairly clearly. They can also help show if cancer has spread to organs near the pancreas, as well as to lymph nodes and distant organs. A CT scan can help determine if surgery might be a good treatment option.

If your doctor thinks you might have pancreatic cancer, you might get a special type of CT known as a multiphase CT scan or a pancreatic protocol CT scan. During this test, different sets of CT scans are taken over several minutes after you get an injection of an intravenous (IV) contrast.

CT-guided needle biopsy: CT scans can also be used to guide a biopsy needle into a suspected pancreatic tumor. But if a needle biopsy is needed, most doctors prefer to use endoscopic ultrasound (described below) to guide the needle into place.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays to make detailed images of parts of your body. Most doctors prefer to look at the pancreas with CT scans, but an MRI might also be done.

Special types of MRI scans can also be used in people who might have pancreatic cancer or are at high risk:

- MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which can be used to look at the pancreatic and bile ducts, is described below in the section on cholangiopancreatography.

- MR angiography (MRA), which looks at blood vessels, is mentioned below in the section on angiography.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound (US) tests use sound waves to create images of organs such as the pancreas. The two most commonly used types for pancreatic cancer are:

- Abdominal ultrasound: If it’s not clear what might be causing a person’s abdominal symptoms, this might be the first test done because it is easy to do and it doesn’t expose a person to radiation. But if signs and symptoms are more likely to be caused by pancreatic cancer, a CT scan is often more useful.

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): This test is more accurate than abdominal US and can be very helpful in diagnosing pancreatic cancer. This test is done with a small US probe on the tip of an endoscope, which is a thin, flexible tube that doctors use to look inside the digestive tract and to get biopsy samples of a tumor.

Cholangiopancreatography

This is an imaging test that looks at the pancreatic ducts and bile ducts to see if they are blocked, narrowed, or dilated. These tests can help show if someone might have a pancreatic tumor that is blocking a duct. They can also be used to help plan surgery. The test can be done in different ways, each of which has pros and cons.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): For this test, an endoscope (a thin, flexible tube with a tiny video camera on the end) is passed down the throat, through the esophagus and stomach, and into the first part of the small intestine. The doctor can see through the endoscope to find the ampulla of Vater (where the common bile duct empties into the small intestine).

X-rays taken at this time can show narrowing or blockage in these ducts that might be due to pancreatic cancer. The doctor doing this test can put a small brush through the tube to remove cells for a biopsy or place a stent (small tube) into a bile or pancreatic duct to keep it open if a nearby tumor is pressing on it.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): This is a non-invasive way to look at the pancreatic and bile ducts using the same type of machine used for standard MRI scans. Unlike ERCP, it does not require an infusion of a contrast dye. Because this test is non-invasive, doctors often use MRCP if the purpose is just to look at the pancreatic and bile ducts. But this test can’t be used to get biopsy samples of tumors or to place stents in ducts.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC): In this procedure, the doctor puts a thin, hollow needle through the skin of the belly and into a bile duct within the liver. A contrast dye is then injected through the needle, and x-rays are taken as it passes through the bile and pancreatic ducts. As with ERCP, this approach can also be used to take fluid or tissue samples or to place a stent into a duct to help keep it open. Because it is more invasive (and might cause more pain), PTC is not usually used unless ERCP has already been tried or can’t be done for some reason.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

For a PET scan, you are injected with a slightly radioactive form of sugar, which collects mainly in cancer cells. A special camera is then used to create a picture of areas of radioactivity in the body.

This test is sometimes used to look for spread from exocrine pancreatic cancers.

PET/CT scan: Special machines can do both a PET and CT scan at the same time. This lets the doctor compare areas of higher radioactivity on the PET scan with the more detailed appearance of that area on the CT scan. This test can help determine the stage (extent) of the cancer. It might be especially useful for spotting cancer that has spread beyond the pancreas and wouldn’t be treatable by surgery.

Angiography

This is an x-ray test that looks at blood vessels. A small amount of contrast dye is injected into an artery to outline the blood vessels, and then x-rays are taken.

An angiogram can show if blood flow in a particular area is blocked by a tumor. It can also show abnormal blood vessels (feeding the cancer) in the area. This test can be useful in finding out if a pancreatic cancer has grown through the walls of certain blood vessels. Mainly, it helps surgeons decide if the cancer can be removed completely without damaging vital blood vessels, and it can also help them plan the operation.

X-ray angiography can be uncomfortable because the doctor has to put a small catheter into the artery leading to the pancreas. Usually the catheter is put into an artery in your inner thigh and threaded up to the pancreas. A local anesthetic is often used to numb the area before inserting the catheter. Once the catheter is in place, the dye is injected to outline all the vessels while the x-rays are being taken.

Angiography can also be done with a CT scanner (CT angiography) or an MRI scanner (MR angiography). These techniques are now used more often because they can give the same information without the need for a catheter in the artery. You might still need an IV line so that a contrast dye can be injected into the bloodstream during the imaging.

Blood tests

Several types of blood tests can be used to help diagnose pancreatic cancer or to help determine treatment options if it is found.

Liver function tests: Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) is often one of the first signs of pancreatic cancer. Doctors often get blood tests to assess liver function in people with jaundice to help determine its cause. Certain blood tests can look at levels of different kinds of bilirubin (a chemical made by the liver) and can help tell whether a patient’s jaundice is caused by disease in the liver itself or by a blockage of bile flow (from a gallstone, a tumor, or other disease).

Tumor markers: Tumor markers are substances that can sometimes be found in the blood when a person has cancer. Tumor markers that may be helpful in pancreatic cancer are:

- CA 19-9

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which is not used as often as CA 19-9

Neither of these tumor marker tests is accurate enough to tell for sure if someone has pancreatic cancer. Levels of these tumor markers are not high in all people with pancreatic cancer, and some people who don’t have pancreatic cancer might have high levels of these markers for other reasons. Still, these tests can sometimes be helpful, along with other tests, in figuring out if someone has cancer.

In people already known to have pancreatic cancer and who have high CA19-9 or CEA levels, these levels can be measured over time to help tell how well treatment is working. If all of the cancer has been removed, these tests can also be done to look for signs the cancer may be coming back.

Other blood tests: Other tests, like a CBC or chemistry panel, can help evaluate a person’s general health (such as kidney and bone marrow function). These tests can help determine if they’ll be able to withstand the stress of a major operation.

Biopsy

A person’s medical history, physical exam, and imaging test results may strongly suggest pancreatic cancer, but usually the only way to be sure is to remove a small sample of tumor and look at it under the microscope. This procedure is called a biopsy. Biopsies can be done in different ways.

Percutaneous (through the skin) biopsy: For this test, a doctor inserts a thin, hollow needle through the skin over the abdomen and into the pancreas to remove a small piece of a tumor. This is known as a fine needle aspiration (FNA). The doctor guides the needle into place using images from ultrasound or CT scans.

Endoscopic biopsy: Doctors can also biopsy a tumor during an endoscopy. The doctor passes an endoscope (a thin, flexible, tube with a small video camera on the end) down the throat and into the small intestine near the pancreas. At this point, the doctor can either use endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to pass a needle into the tumor or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to place a brush to remove cells from the bile or pancreatic ducts.

Surgical biopsy: Surgical biopsies are now done less often than in the past. They can be useful if the surgeon is concerned the cancer has spread beyond the pancreas and wants to look at (and possibly biopsy) other organs in the abdomen. The most common way to do a surgical biopsy is to use laparoscopy (sometimes called keyhole surgery). The surgeon can look at the pancreas and other organs for tumors and take biopsy samples of abnormal areas.

Some people might not need a biopsy

Rarely, the doctor might not do a biopsy on someone who has a tumor in the pancreas if imaging tests show the tumor is very likely to be cancer and if it looks like surgery can remove all of it. Instead, the doctor will proceed with surgery, at which time the tumor cells can be looked at in the lab to confirm the diagnosis. During surgery, if the doctor finds that the cancer has spread too far to be removed completely, only a sample of the cancer may be removed to confirm the diagnosis, and the rest of the planned operation will be stopped.

If treatment (such as chemotherapy or radiation) is planned before surgery, a biopsy is needed first to be sure of the diagnosis.

Lab tests of biopsy samples

The samples obtained during a biopsy (or during surgery) are sent to a lab, where they are looked at under a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells.

If cancer is found, other tests might be done as well. For example, tests might be done to see if the cancer cells have mutations (changes) in certain genes, such as the BRCA genes (BRCA1 or BRCA2) or NTRK genes. This might affect whether certain targeted therapy drugs might be helpful as part of treatment.

See Testing Biopsy and Cytology Specimens for Cancer to learn more about different types of biopsies, how the biopsy samples are tested in the lab, and what the results will tell you.

Genetic counseling and testing

If you’ve been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, your doctor might suggest speaking with a genetic counselor to determine if you could benefit from genetic testing.

Some people with pancreatic cancer have gene mutations (such as BRCA mutations) in all the cells of their body, which put them at increased risk for pancreatic cancer (and possibly other cancers). Testing for these gene mutations can sometimes affect which treatments might be helpful. It might also affect whether other family members should consider genetic counseling and testing as well.

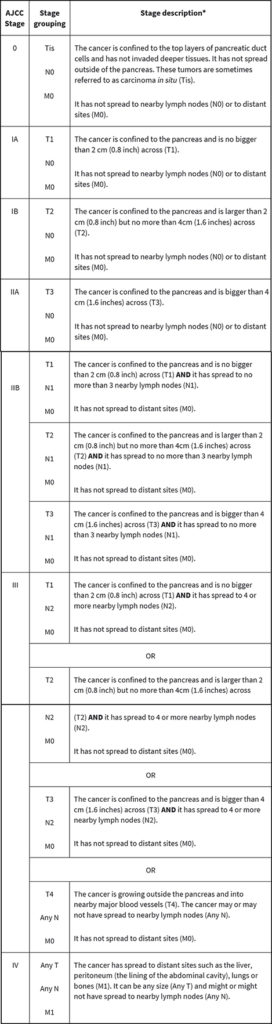

Pancreatic Cancer Stages

After someone is diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treatit. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

The earliest stage pancreas cancers are stage 0 (carcinoma in situ), and then range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means a more advanced cancer. Cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

How is the stage determined?

The staging system used most often for pancreatic cancer is the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent of the tumor (T): How large is the tumor and has it grown outside the pancreas into nearby blood vessels?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes? If so, how many of the lymph nodes have cancer?

- The spread (metastasized) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs such as the liver, peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), lungs or bones?

The system described below is the most recent AJCC system, effective January 2018. It is used to stage most pancreatic cancers except for well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), which have their own staging system.

The staging system in the table uses the pathologic stage. It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. This is also known as the surgical stage. Sometimes, if the doctor’s physical exam, imaging, or other tests show the tumor is too large or has spread to nearby organs and cannot be removed by surgery right away or at all, radiation or chemotherapy might be given first. In this case, the cancer will have a clinical stage. It is based on the results of physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests (see Tests for Pancreatic Cancer). The clinical stage can be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread further than the clinical stage estimates, and may not predict the patient’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage. For more information, see Cancer Staging.

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

Cancer staging can be complex. If you have any questions about your stage, please ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand. (Additional information of the TNM system also follows the stage table below.)

Stages of pancreatic cancer

* The following additional categories are not listed on the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Other prognostic factors

Although not formally part of the TNM system, other factors are also important in determining a person’s prognosis (outlook).

Tumor grade

The grade describes how closely the cancer looks like normal tissue under a microscope.

- Grade 1 (G1) means the cancer looks much like normal pancreas tissue.

- Grade 3 (G3) means the cancer looks very abnormal.

- Grade 2 (G2) falls somewhere in between.

Low-grade cancers (G1) tend to grow and spread more slowly than high-grade (G3) cancers. Most of the time, Grade 3 pancreas cancers tend to have a poor prognosis (outlook) compared to Grade 1 or 2 cancers.

Extent of resection

For patients who have surgery, another important factor is the extent of the resection — whether or not all of the tumor is removed:

- R0: All of the cancer is thought to have been removed. (There are no visible or microscopic signs suggesting that cancer was left behind.)

- R1: All visible tumor was removed, but lab tests of the removed tissue show that some small areas of cancer were probably left behind.

- R2: Some visible tumor could not be removed.

Resectable versus unresectable pancreatic cancer

The AJCC staging system gives a detailed summary of how far the cancer has spread. But for treatment purposes, doctors use a simpler staging system, which divides cancers into groups based on whether or not they can be removed (resected) with surgery:

- Resectable

- Borderline resectable

- Unresectable (either locally advanced or metastatic)

Resectable

If the cancer is only in the pancreas (or has spread just beyond it) and the surgeon believes the entire tumor can be removed, it is called resectable. (In general, this would include most stage IA, IB, and IIA cancers in the TNM system.)

It’s important to note that some cancers might appear to be resectable based on imaging tests, but once surgery is started it might become clear that not all of the cancer can be removed. If this happens, only some of the cancer may be removed to confirm the diagnosis (if a biopsy hasn’t been done already), and the rest of the planned operation will be stopped to help avoid the risk of major side effects.

Borderline resectable

This term is used to describe some cancers that might have just reached nearby blood vessels, but which the doctors feel might still be removed completely with surgery.

Unresectable

These cancers can’t be removed entirely by surgery.

Locally advanced: If the cancer has not yet spread to distant organs but it still can’t be removed completely with surgery, it is called locally advanced. Often the reason the cancer can’t be removed is because it has grown into or surrounded nearby major blood vessels. (This would include some stage III cancers in the TNM system.)

Surgery to try to remove these tumors would be very unlikely to be helpful and could still have major side effects. Some type of surgery might still be done, but it would be a less extensive operation with the goal of preventing or relieving symptoms or problems like a blocked bile duct or intestinal tract, instead of trying to cure the cancer.

Metastatic: If the cancer has spread to distant organs, it is called metastatic (Stage IV). These cancers can’t be removed completely. Surgery might still be done, but the goal would be to prevent or relieve symptoms, not to try to cure the cancer.

Tumor markers (CA 19-9)

Tumor markers are substances that can sometimes be found in the blood when a person has cancer. CA 19-9 is a tumor marker that may be helpful in pancreatic cancer. A drop in the CA 19-9 level after surgery (compared to the level before surgery) and low levels of CA 19-9 after pancreas surgery tend to predict a better prognosis (outlook).

Source: American cancer society, pancreatic cancer early detection, diagnosis, and staging, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging.html